Do you enjoy riding bareback? Do you ride in a treeless saddle? Do you wonder how your horse can understand small movements in your seat when you ride? Here’s a quick tip to have a bit of insight into bareback riding.

I had the opportunity to photograph my 5’4” skeleton on top of a fully articulated horse’s skeleton with a little help from Brad. He got the job of holding it in position. It was quite educational to see how the two skeletons mesh.

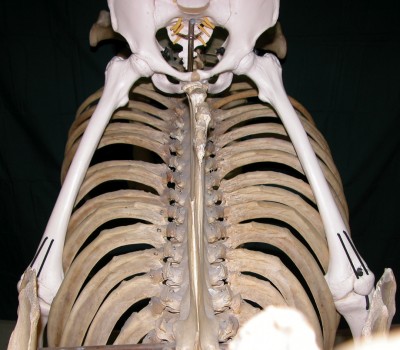

The part of the horse we sit on is the ribcage and back. The horse has 18 pairs of ribs each of which attaches to a vertebra collectively known as the thoracic vertebrae, which is between the cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) vertebrae.

The thoracic (T) vertebrae have spinous processes, which angle either towards the tail (T1 – 13) or towards (T15 – 18) the head. The place where the direction changes is called the anti-clinal moment and is at approximately the 13 – 14th thoracic vertebrae. You can roughly determine where this is by looking for the deepest point in your horse’s back.

The height of the 1st spinuos process is fairly short but they rapidly increase to a maximum height at T3 – 4 and then gradually decrease towards the latter part of the thoracic spine. The withers are considered the spinal processes of T 5 – 9. The ribs are much thicker and narrower at the front where the shoulder blades lay against them, becoming thinner and broader towards the back. Each rib has a distinct curve shape that turns down and in towards the spine. The horse’s back muscles fill in the space between the curve of the ribs and the spine. The shape of the horse’s ribcage determines how you will sit when riding bareback.

The slope, height and length of the withers determines the placement of the rider’s seat, which on this skeleton is approximately T13 – 14 (the anticlinal moment). But the shape of the ribcage at this point is quite broad while the ribs further towards the head are narrower and more upright. Most people don’t have the ability to comfortably straddle this shape due to the narrowness of the human pelvis and hips. Therefore the rider’s leg naturally goes forward when riding bareback where the ribcage is narrower.

The rider’s weight is born on the seat bones, which rest on the horse’s back on either side of the spine. There isn’t very much room between the seat bones and the spine as is evidenced from Photo 3. If the horse is fleshy or has low withers this area will be broad and flat. But if the horse is thin or has high withers it can be a bit painful because there is less padding. A treeless saddle can make this a bit more comfortable but if the horse’s spine tends to stick up above the flesh you have to be careful you don’t put pressure directly on the spine. The purpose of the gullet in a saddle is to ensure that there isn’t any pressure directly on the spine, which I am sure you can appreciate if you have ever hit your shin on the leg of a table.

The horse can feel small changes of weight and shifts in your body position when riding bareback. Bareback riding is also a way to develop a sense of balance but it is important that you feel comfortable and safe. Riding bareback can be an enjoyable way to ride especially in winter. The heat of the horse’s body can help keep you warm. But if riding bareback is painful or frightening I suggest you stick with your saddle. And always remember to – enjoy the ride!

- The withers appear as a straight line down the middle while the spring of the ribs is more obvious. Observe how narrow and close to the spine the rider’s seat bones are and that the hip joints are not wide enough apart to span the breadth of the ribs at this point.