Q: Why is it so difficult these days to find a saddle that correctly fits both the horse and the rider?

Q: Why is it so difficult these days to find a saddle that correctly fits both the horse and the rider?

A: First of all, a saddle is actually a very complicated thing to make. It needs to sit on a living breathing beast without interfering with the horse’s movement, it has to allow the rider to sit in the correct position to be in balance with the horse and it has to transmit information between the rider and the horse. If any one thing is not correct, the proper signals are interrupted. Then, you ask all of this to work while the beast is moving or going over a jump. It really becomes very involved rather quickly. Secondly, a large percentage of production saddle makers don’t know anything about horses and most top riders don’t know anything about making saddles. There are lots of popular saddles on the market endorsed by top riders but they have never made a saddle. They don’t understand how complicated the problem is. This fad and fashion for postage-stamp-size saddles is causing a lot of problems. In the quest for lighter, closer-contact saddles, the horse is being crucified because the saddles aren’t man enough to do the job. The panel material that most close-contact saddles are made of today, in short order, compresses down to nothing at the points of the tree. This puts tremendous pressure on the horse’s shoulders. Also, the saddles no longer distribute the weight of the rider properly. The bigger the rider, the greater the problem. Historically, saddles were larger with very wide gullets and large panels. Think about pack horses that carry tremendous weight on pack saddles or the old cavalry saddles. They both had wide-open gullets and broad panels to distribute the weight over as much surface area as possible. If you were to use one of today’s close-contact saddles for a pack horse you would barely get him out of the barn before you crippled his spine.

Q: Why did British saddle makers move away from the old design of larger, broader saddles?

A: A number of years ago, the British saddle industry copied a saddle that became popular. However, this “close-contact” design was not the best for the horse. The saddle makers simply copied what was popular. You see, the biggest problem with most British saddle makers, if you like, is that they are actually saddle assemblers. They no more know what the back of a horse looks like than a banker. When they finish with their schooling, they go straight into a production shop, most of which are here in Walsall, and work for a foreman who takes the pattern off the wall and tells them to make 20 of these. The foreman is someone just like themselves, who has been in the shop for a while, but he has never been out of the shop to see what a horse looks like or how the saddles he is making fit the horse. Each saddle maker is a piece-worker. He is paid his wages based on the number of saddles he makes, not the quality of the saddle produced. He is paid approximately 30 to 35 pounds or about $45.00 US for each saddle. These saddlers never see what happens to a horse ridden in one of their saddles.

Q: Why aren’t the designs of saddles changing to fit horses?

A: The link between the consumer and the saddle maker in the mass-market saddle shops is broken. If you have a problem with your saddle you take it back to the tack shop where you bought it. They will try and solve your problem with another saddle there in the shop. The saddle you had is sold to another customer. The problem is hardly ever relayed back to the saddle maker who made the saddle. There you have it then, the problem continues to be built into the saddle because the makers never were told there was a problem with the saddle.

Q: How does your saddle shop differ from the rest of Walsall?

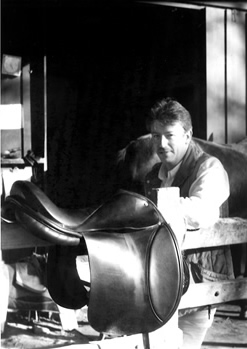

A: It differs inasmuch as we specialize in dealing directly with the ultimate customer who is going to ride in the saddle and every saddle made is fitted by me so that I can see first-hand any problems that might arise. Each saddle is made by an individual saddle maker and I oversee every saddle made in the shop from start to finish. That is, rather than making 12 or 18 or 24 jumping saddles at a time and sending them out to the consumer, each saddle is made specifically for the horse and its rider. The reason for this is that everyone has different measurements: knee to hip, knee to ankle, and body weight. Also, everyone’s center of balance is different so we always have to take into account what’s right for that individual. There isn’t one saddle that is correct for everybody. We make each saddle correct for each individual and the only way I can do it is by measuring each horse and rider myself, then tailoring a saddle for them.

Q: How long does it take you to make a saddle?

A: It takes about 10 working days start to finish. There are several stages where the saddle has to sit overnight while something dries.

Q: What is the most common reason why someone calls you for one of your saddles?

A: Horse back trauma. Most saddles aren’t made horseback shape if you like. I get called in because the horse is in pain and the rider realizes it is the saddle is causing the problem.

Q: How do you measure a horse for a saddle?

A: What most people do, including some so-called custom saddle makers, is take a wire coat hanger or flexi-curve and measure the horse at the wither where the points of the tree will sit. If you think about it, that’s like taking only 1/17th of the information you will need for a 17-inch saddle. This method really doesn’t provide enough information to fit your horse. There is so much more that needs to be taken into consideration.

That is why, 11 years ago, I devised an instrument to measure the horse’s back. The back-measure calibrates the horse’s back over the entire area that the saddle needs to fit. The back-measure takes calibrated measurements at 45 different points and translates the horse’s back shape into a series of numbers. Then, when I am back in the shop, I can reset the back measure to the shape of the horse’s back while I am making the saddle. This was the only way I could think of to have the horse’s back shape in the shop with me while I was making the saddle without having to deal with the mess of the real horse.

Q: What is the most important thing to consider when fitting a horse for a saddle?

Q: What is the most important thing to consider when fitting a horse for a saddle?

A: There are five things you have to take into account: the shoulder, the wither, the spine, the long back muscles and the natural curve line of the horse’s back. The spine must be unhindered. It functions like a suspension girder. Put pressure on any part of the spine and it no longer works. If the gullet of the saddle is too narrow it can put pressure on the spine or on the nerves that run alongside of the spine. The gullet needs to be at least three man’s-fingers wide to allow for movement of the spine, especially for dressage when the horse is being asked to move in small circles causing the spine to curve. If the gullet is too narrow, the saddle will wind up on top of the spine and cause the horse to drop his back.

Next, you have to consider the shoulder. If the saddle impinges on the shoulder, the shoulder will lock up. In a dressage saddle the points of the tree are straighter than in a jumping saddle. There is less chance of a dressage saddle blocking the shoulder than a jumping saddle where the flap of the saddle will go across the shoulder to allow the rider to remain over the horse’s center of gravity. In either case, any pressure on the shoulder will hinder the horse’s movement. Therefore, the panel needs to be cut out at that point where it crosses the horse’s shoulder in order not to apply any pressure. Then the panel acts as a socket for the shoulder which acts like a ball, creating a ball and socket joint.

Next, you have the wither. The most important thing about the wither is that it must be missed. It is a non-functional part of the horse except in side-saddle where it acts like a shark’s fin and holds the saddle in place. Otherwise the wither simply gets in the way. The wither determines how close you can get to your horse. If you have a high-withered horse and a close-contact saddle, I guarantee you no longer have close contact once the saddle has been leveled through. You see so many people riding in these so-called close-contact saddles with miles of pads stuffed underneath trying to make up for a fault that was built into the saddle in the first place. The bigger the wither the thicker the panel needs to be in order to make the saddle level. How much you clear the wither by doesn’t matter as long as it remains clear at all times. Trying to get three-fingers clearance on some of these big horses would put the rider up so high they could get a nose bleed.

Finally, the pressure must be even on the long back muscles. The horse’s back is three-dimensional, like an airplane propeller with a twist through it. The panel shape has got to match the angle of the horse at the front and follow the contour of the horse’s back all the way through to the rear of the saddle. The saddle must be long enough to properly spread the weight out across the long back muscles.

Q Then, who decides what size saddle you should buy?

A: The horse determines the size of saddle that you need, not the rider. Take, for instance, the typical small woman riding the enormous warm-blood horse. If the rider were to determine the size of the saddle, say for instance a 16-1/2″, the saddle would end in the middle third of the horse’s back. This would create a pressure point on the horse’s back because the weight is not distributed properly across the entire area. Instead, what should happen is that the horse should be fitted for the size of tree that it needs to properly span the back, say perhaps and 18-1/2″ tree. Then, an inner seat is constructed for the rider so that she does not swim around in that 18-1/2″ saddle. This way both the horse and the rider are properly fitted.

Q: How do I then get “close-contact” with my horse?

A: If you want close-contact, get a really round-barreled horse with almost no wither. Then I can get you nearly gas-tight to the horse. The horse’s wither determines how close you can get to the horse’s back. Remember, the wither’s only purpose is that it needs to be cleared. From a saddle-maker’s perspective, it only just gets in the way. When you try to fit one of these big-withered thoroughbred types you have to allow for the wither. Then the thickness of the panel is determined by what depth is required to level the saddle through. It’s a joke to think you can have a thin little panel on one of these big horses. They suffer the worst, in some cases, from this fad of smaller, lighter saddles. Often times, once you level the saddle, the points of the tree become so short that all the pressure is being placed directly on the bony area of the wither rather than coming down and distributing the pressure onto the long back muscles.

Q: Are all saddle trees alike?

A: No. The tree is the framework around which the saddle is constructed. All trees used to be made from beech wood. The wood in that tree has “memory” and the grain of the wood helps to hold the tacks. Some saddle makers have gone away from using the beech wood trees but in my opinion nothing can take the place of beech wood. The problem with the synthetic materials is that the tacks won’t hold in the plastic. You can rip tacks right out, so synthetic trees can become very unsafe when going cross-country. The other problem with a lot of saddles is the width of the tree. If you start with the standard 9-1/2″ tree (measuring under the seat bones at the widest part of the tree) and you attempt to put a gullet wide enough to clear the horse’s spine (three man’s-fingers), you run out of room for the panels. The panels wind up being about 2 to 3 inches wide. This is not enough width to properly distribute the rider’s weight and will cause back problems in the horse. I make all my saddles on a beech wood tree. The widest part of the seat, depending upon the horse and rider, ranges from 11″ to 12-1/2″ wide. This allows plenty of room for a wide gullet and a broad panel.

Q: What is the best material for making a panel?

A: Lots of saddles are made with wool flocking. The problem with wool is that it can go hard, ball up inside the panel and become uneven, putting point pressures on the horse’s back. Now, say you have a saddle with a stuffed wool panel and you take it to be reflocked because, for example, it is sitting down at the back. The panel itself is a predetermined leather bag. When the saddler tries to reflock the panel, he inserts more wool into the bag in an attempt to raise up the back of the saddle. As he does this, the panel becomes more rounded because it is a fixed size. Then, rather than having a flat panel on the horse’s back, the panel’s shape becomes more like a rolling pin. Instead of distributing the pressure over a large area, the panel winds up placing all the pressure at one point just like when you put a round object onto a flat surface. Secondly, because of they way saddles are reflocked, taking a small piece of wool and inserting it into the panel with a long tool through a slit in the leather , the saddler has created round hard balls of wool in the panel that are like marbles on the horse’s back.

In my saddles, I use a 100%-memory foam core with a softer kinder outer foam just before the leather of the panel. When we make the panels in the shop the inner foam core is shaped to fit the horse’s back using the back measure. With 100%-memory foam the panels always return to their original shape and the saddle never has to be reflocked. If, later on, the customer gets a different horse or the original horse changes shape, the panels are taken off and reshaped to fit. If any panel, foam or wool, is not made to the contour of the horse’s back, then either one can be wrong and cripple a horse . That’s why working with the back measure is so totally important, to get the contour correct.

Q: How can someone tell if their saddle fits their horse?

A: First and foremost you need to see that the spine is free, the wither is clear, the shoulder is not getting pinched and the panel fits the shape of the horse. The best way to do that is to ride without a pad and look at the underside of the saddle and your horse’s back after you finished. The sweat and dirt marks on the panels should be even throughout, not really dirty areas at the points of the tree or at the back of the saddle and the rest of it clean. The horse should have an even saddle pattern on its back, no pressure marks near the spine or wither. Dry areas can indicate either no pressure or too much pressure. In either case, the pressure on the horse’s back is not even at that point. If the saddle is too small for the horse the saddle marks will not span the length of back properly, putting pressure usually in the middle third of the horse’s back. This is the cause of a lot of sore backs in large horses ridden by little ladies.

Q: How can someone tell if the saddle fits the rider?

A: Most all riders these days ride in saddles that are too small for them. The most important thing to remember for fitting the rider is the seat bone to stirrup bar relationship. This depends not so much on the size of the rider’s seat as it does their length of thigh. If the rider has a long thigh, a much bigger saddle is needed than for a person with a short, round thigh. Otherwise, the rider will wind up at the back of the saddle putting point pressure on the horse’s back, instead of sitting in the middle of the saddle with the weight evenly distributed across the horse’s back. In a dressage saddle, if the stirrup bar is placed too far forward on the tree of the saddle, the rider will wind up in a “chair” seat. In a jumping saddle with the stirrup bar too far back, the rider will be thrown forward over the saddle You will see the lower leg flick out behind.

Q: What can result from riding in a poorly fitted saddle?

A: In the best case, the rider is put into the wrong position. In the worst case, the horse can be crippled. Lots of times the riders think that it is their fault that they can’t do what the instructor is asking them to do. Sometimes the saddle makes it impossible for them to sit properly. Think about how much time and money is wasted, not to mention the discomfort to the horse, rider and vet bills, because the horse and rider were in a saddle that didn’t fit. Quite often, after I fit someone in one of my saddles, I get a letter back telling me how much better she can ride now simply because the saddle allows her to be where the instructor has been trying to get her for years.

Q: What can cause a rider to feel crooked in a saddle?

A: This is a very complicated question. There are two areas to consider: the saddle is not made properly and/or the horse’s shoulders are uneven. First, the saddle could have been built on a crooked tree, or the stirrup bars could have been riveted unevenly on the tree putting one leg of the rider further forward , or the girth straps could have been set on unevenly, pulling the saddle into a twist when you girth up the saddle. Also, the horse could have uneven shoulders. This results in one side of the saddle hitting the high spot on one shoulder, then the other side continues sliding forward seeking the other shoulder. If the gullet is not wide enough as the saddle goes into a twist, the panels will put pressure right across the spine and totally block the horses back.

When making a saddle for a customer all these potential problems in turn have to be looked at and made sure that they don’t occur. We carefully measure every phase of the saddle as it is made to prevent these kinds of problems. If the horse’s shoulders are uneven, as long as the problem is addressed, changes can be made in the panels.

Q: What are some signs to look for which may tell you that you have a saddle fitting problem?

A: From the rider’s point of view: discomfort in the seat or crotch or not being able to maintain the correct position, i.e. being tipped backwards or forwards, the legs being pulled forward, the seat going backwards. From the horses’ point of view: the horse won’t want to lower its head when ridden, won’t raise its back, goes better on one rein than the other, or is reluctant to go on one rein at all, the horse pins its ears back when you approach it with the saddle.

Q: In what discipline is it the most critical that the saddle fit correctly and in what discipline do riders experience the most difficulty?

A: That’s got to be dressage because it is so much more precise than the other disciplines. If the saddle is the least bit wrong it can put pressure on the horse and make it virtually impossible for him to bring his back up under the rider. If the saddle isn’t quite right for the rider, she will not be able to properly communicate to the horse.

Q: What if someone rides several different horses, do they need a saddle for every horse?

A: Quite often you find that a rider who rides different horses tends to ride similar kinds of horses, say warm-bloods or thoroughbreds. Then what you can do is make a saddle that fits that particular breed. Every breed has a built-in back shape; for example, the generally keyhole-shaped wither is the back trait of the thoroughbred, and the well-muscled barreled back is typical of Morgan horses, whereas warm bloods tend to the broad, long, flat backs. So if you ride several horses, you have to fit for the breed you most often ride. In one stable in England, a lady asked me to fit her for a saddle. She rode 8 different horses. We used the back-measure on the most difficult horse to fit, then placed it on the other 7 horses. The back-measure showed that the saddle would fit 7 of her 8 horses perfectly well.

Q: If there were only one thing you could tell a rider in regards to saddle fitting, what would it be?

A: Listen to your horse! Even if you don’t know anything else about fitting, look for the signs: a cranky horse with its ears back, fidgety when being saddled up, dropping its back out when you get on, or flinching and dropping away when you run your hand down its back after you have ridden.

Copyright© 1995. All rights reserved.